In the mid-2000s, James Tisch (Loews Corporation) recounted his firm’s entry into the oil tanker & offshore oil rig business in a keynote speech to the Chartered Institute of Management Accountants (CIMA).

Thank you and good morning.

I’ve always wanted to start a speech off with the following Beatles quote – and today I’m gonna do it: “It’s wonderful to be here; it’s certainly a thrill.” I feel like I am an imposter who is taking my 21-year-old son’s job. You see, at the age of 18, when he was thinking of what he wanted to do for a career, he settled on the profession of keynote speaker. So here I am today, scooping his first gig.

For those of you who may not know, Loews Corporation is a diverse holding company, which owns six very different subsidiary companies – and not one of them sells lumber or shows movies. And while our six subsidiaries may vary, our business strategies are actually quite similar. At Loews, our investment strategy is based upon analyzing economic variables of a particular industrial sector and then investing for the purpose of long term return on investment to our shareholders. Sounds simple – well, yes and no.

It is simple because we tend to look at investment opportunities using basic microeconomic principles, like supply and demand and, . . . It is not simple because – – as we all know — investing in industries like energy can be highly cyclical and very risky.

I said that Loews tends to look for “long term” return on investment; we do that by seeking to acquire businesses that are temporarily undervalued and that have a strong senior management team. We then invest the capital necessary in order to achieve our goal of generating the highest possible returns on our equity investment. This is a strategy that’s been successful for us, and it’s the one that initially led us to explore the energy sector.

Let’s go back to 1975, when there was a building boom in supertankers, brought about by relatively low oil prices that had caused large increases in oil demand. A few years later, in the late ‘70s, there was an oil embargo and resulting oil price hike, which drastically reduced the amount of oil coming out of the Persian Gulf – much less oil, but still lots of tankers, now just bobbing in the water. It was soon afterward, in the early ‘80s, that we started thinking about buying tankers. We had seen from reading newspapers that the worldwide supply of tankers was vastly overbuilt; according to quoted estimates, the market required only 30% of the ships that were afloat. As a result, ships were trading at scrap value.

That’s right. Perfectly good seven-year-old ships were selling like hamburger meat – dollars per pound of steel on the ship. Or, to put it another way, one was able to buy fabricated steel for the price of scrap steel. We had confidence that with continued scrapping of ships and increased oil demand, one day the remaining ships would be worth far more than their value as scrap. We were sure of three other things: First, by buying at scrap value, there was very little downside. Second, we knew that the ships would not rust away while we waited for the cyclical market to turn. And third, we knew that no one would build more ships with existing ships selling at a 90% discount to the new build cost. We were confident that the demand for oil, particularly from the Persian Gulf, would ultimately increase with worldwide economic growth and so the remaining tankers would ultimately be worth much more than their scrap value.

So we did the logical thing — we took out the yellow pages, looked under “Brokers – Tankers,” and from there, made our way to Scotland to get a first hand look and “kick the tires” of some of these big ships that are almost four football fields long. And on board one of these massive vessels was formulated the Jim Tisch $5 Million Test. And what is the Jim Tisch $5 Million Test, you may ask? While on the ship you look to the front and then you look to the rear – then take a look to the right and then to the left –then you scratch your head and say to yourself – “Gee! You mean you get all this for $5 million?!”

Just to give you some perspective, these ships, capable of hauling 2-3 million barrels of oil, had been built eight years earlier for a cost of over $50 million. In all, we purchased six tankers in the early 80’s, all by using the Jim Tisch $5 Million Test. By 1990, the market had turned, as – you guessed it – too many ships were scrapped and the volume of oil coming out of the Persian Gulf increased. And, as good capitalists, when this happened we sold a 50 percent interest in our ships for 10 times the valuation of our initial investment. Fast-forward to 1997 when opportunity knocked again. We witnessed a set of conditions similar to those of the mid-‘70s – little construction of new oil tankers despite increased production of oil from the Persian Gulf. That year we decided to build four new ships in reaction to the distinct lack of new building. We sold those ships about a year and a half ago – relying on the same principles applied as before, except in reverse. Oil prices were going up, but then, so was the supply of ships. We could sense that the increased prices for oil would negatively affect demand for oil, and ultimately ships, and therefore bring down the value of our ships. We sold — probably a year too soon — but in this business, I would prefer to be early rather than late.

In 1988 we saw a similar situation develop in a related industry — offshore drilling. In the 80’s, offshore drilling rigs had declined in value dramatically as oil and gas prices were relatively low and worldwide hydrocarbon reserves were flush. But we saw that the demand for oil and natural gas was increasing as a result of these lower product prices. We knew that the demand for rigs would return, and we knew that – like the tankers before them – the rigs would not rust away in the interim. So we took a trip to the Gulf of Mexico where we went aboard a jack-up oil rig and, yes, we applied the Jim Tisch $5 Million Dollar Test. Remember? You look to front – you look to the back — you know the rest. A few weeks later, we had bought an offshore rig company named Diamond M, and became the proud owners of 10 drilling rigs for a total investment of about $50 million. A few years later, with the business still bouncing along the bottom, we bought another offshore oil drilling company, Odeco, which increased our investment in the rig business tenfold, moving us from a $50 million investment to an investment worth $500 million. We renamed the company Diamond Offshore. By 1995, the cyclical drilling market had changed, and we were making some money in the business. So, as good capitalists, we took the company public where we were able to get all of our money back from our initial investment and still retain a 55 percent stake in the company. Today, Diamond Offshore has a valuation of about $10 billion, $5 ½ billion of which is held directly by Loews.

Oil drilling – like tankers — is a cyclical business. Our rigs are contracted by oil companies who pay a day rate which is determined by the supply and demand for oil rigs. An oil rig takes at least three years to build, so the supply of these rigs is relatively fixed over the short-to-intermediate term. However, the demand for rigs can gyrate wildly based on the temperament of oil company managements in response to oil prices, world events, and other factors. Day rates can go up or down by a factor of five or more, just as we’ve seen in the past year and a half. Whereas in mid-2004 we 13 contracted a jack-up rig at $27,000 per day, today that same rig commands over $100,000 per day. We got into the business because we believed the rig assets were undervalued. Over time, we were willing to ride out some very lean years, patiently waiting for the turnaround and humming the Ruby and the Romantics standard, “Our Day Will Come”. (Speech continues, see link below)

James Tisch (CIMA keynote speech)

“It’s like déjà vu all over again.” – Yogi Berra

Today, the offshore drilling industry is similarly under duress. The main players are Transocean, Seadrill, ENSCO, Noble Corporation, Diamond Offshore, Rowan Corp & Atwood Oceanics.

A quick review of their investor relations webpages provides the following fleet overview.

The table below lists the debt, market capitalization and “Market” based enterprise value which essentially accounts for the market value of each company’s debt, not the notional amount.

Regressing the “Market” EV against the number of rigs, provides an estimate of the market imputed valuation of the various rigs.

Ultra-deepwater : $190 million

Deepwater & midwater : $94 million

Jackups : $45 million

I’ll need to find data on replacement costs to confirm whether or not these are low valuations. I think they are but who knows.

A separate but important thing to note on the industry is the implications of the market cycle. My quick, naive summary of the industry cycle is as follows ….. When oil heads lower, E&P companies cut back by either restructuring existing contracts or not renewing contracts for offshore rigs, the rig companies suffer with unused rigs accumulating, and at some point cry uncle and scrap some of their older rigs. Across the industry, there’s a reduction in the number of offshore oil rigs available and when a recovery in oil materializes, the industry is caught with its pants down and without enough oil rigs, prompting new orders, higher margins. At this point, it’s rinse and repeat.

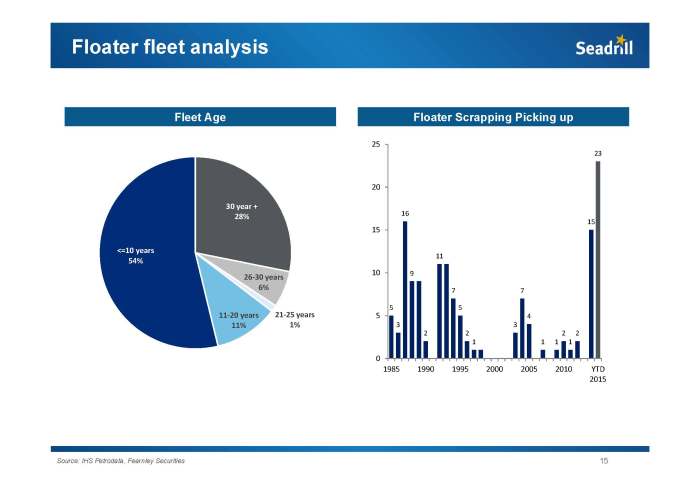

For an industry wide overview on the age of fleets see page 15 & 16 of the following Seadrill presentation, excerpted below. Nearly a third of all floater rigs are over 30 years old and over half of all jackup rigs are over 30 years old. This suggests there could be a significant number of rigs scrapped during this downturn, hopefully making the recovery all the more interesting.

I believe an interesting way to play this is via corporate debt. To give you an idea, here are some recent levels.

- Ensco 4.70% 3/2021 : 68 cts on the dollar

- Ensco 4.50% 10/2024 : 63 cts

- Ensco 5.20% 3/2025 : 60 cts

- Ensco 5.75% 10/2044 : 56 cts

- Diamond 5.875% 5/2019 : 90 cts

- Diamond 3.45% 11/2023 : 73 cts

- Diamond 5.70% 10/2039 : 64 cts

- Diamond 4.875 11/2042 : 58 cts

Disclosure – I own some of the oil rig bonds and may purchase more.